On the path of most resistance with the gay mayor changing Poland

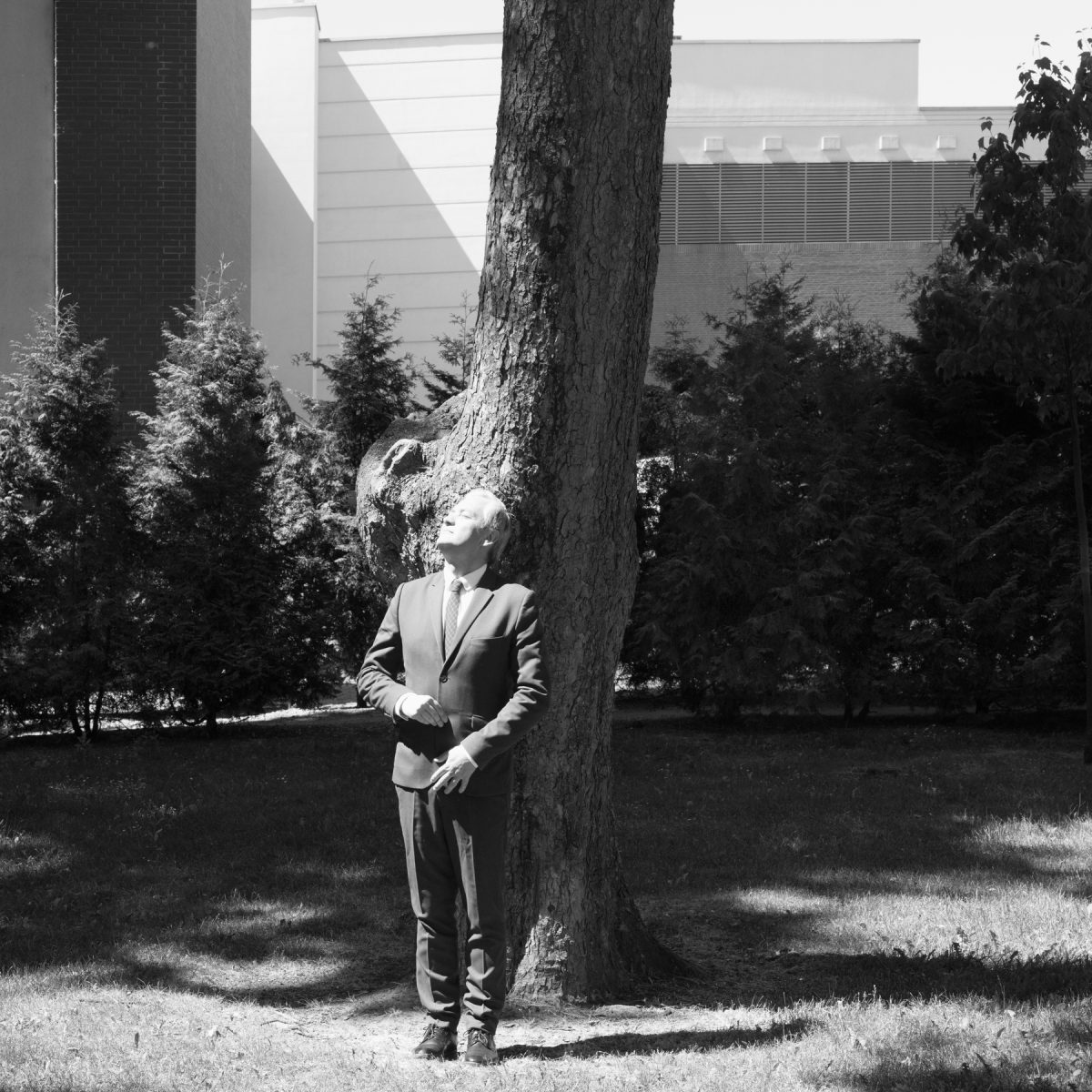

Robert Biedron (42) has announced the creation of his own political “pro democratic” movement against Polish conservatives on 5th of September 2018. © Jakob Ganslmeier

Progressive, pro-refugees and openly gay, the former MEP and current mayor of Słupsk – a remote town near the Baltic coast – Robert Biedroń is an outlier in the Polish political scene. Here is the story of a man who rekindled a town’s pride, incidentally saving it from bankruptcy.

The Church of St. Mary is on Robert Biedroń’s way to work. A group of elderly women stand in front of it, along with 90-year-old Jan Giriatowicz, a former parish priest and freeman of the city. Every month, churchgoers meet in front of the town hall to pray for the city of Słupsk and “compensate for the sin of sodomy” of its highest official. Biedroń greets them and smiles. “Let’s pray for the president,” Giriatowicz says, while Biedroń – an atheist – and the devotees hold each other’s hands in prayer.

Peace amidst chaos

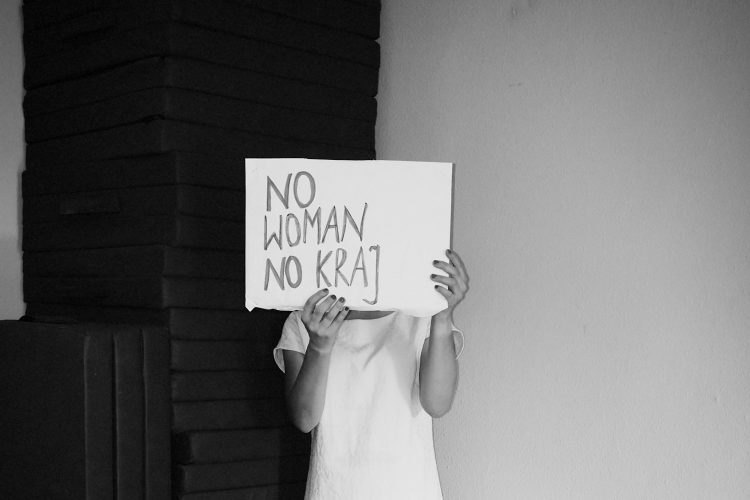

This symbolic scene points towards the fact that this controversial “leftie” and “homocelebrity”, as his enemies like to call him, is sure to get re-elected in the local elections this autumn. However, Biedroń changed his plans last minute. He dropped out of the race and announced his intention to create his own political party, ready to fight on a national level. His reverence is surprising, considering the growing popularity of the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party. The party’s political standing contradicts Biedroń’s. Theirs is bursting with xenophobia and populism, and their discourse revolves around god and the nation. However, the people of Słupsk love their mayor and have forgiven him for not being a local while also being homosexual, even if homosexuality is a serious burden for any politician in the country. Or maybe they just love him back.

“We may be different, but we should be searching for common ground,” Biedroń says, philosophically commenting on the scene in front of the church. “There are some Jehovah’s Witnesses who stand in front of the town hall. They abstain from voting and consider homosexuality a sin, so I could just ignore them. Instead, I provided them with a bench. My duty as a mayor is to make sure everybody has a place and lives well in my city, including Jehovah’s Witnesses.” His gentle voice and kind smile mingle well with the sacred architecture of the 127-year-old town hall decorated with Gothic windows and stained glass. Sitting in the mayor’s cabinet, Biedroń looks like a good-hearted priest. To get there, we have to cross a hallway of photographs displaying half-naked men and women that are part of a temporary exhibition by a young local photographer. In his cabinet, a photo of Biedroń and his life partner is neatly placed on the bookshelf.

The world first heard about Biedroń in 2011, when the prominent LGBT rights activist became the first openly homosexual MP in Polish parliament. Three years later, he took up the position as mayor of Słupsk, a relatively unknown city in the region of Pomerania. Prior to his victory, the press had only written about the city on one occasion – during the 1998 street riots – which were the most notable case of police brutality Poland had seen since the fall of communism. Now, with Biedroń in the limelight, Słupsk constantly makes it to the headlines.

“I didn’t expect him to win when he was running for mayor,” Cezary Piechociński, an author of books about Słupsk and owner of a collection of urban busses, recalls. “I didn’t like him, I thought he was a vulgar tattler. Still, I voted for him and I will do it again in the next elections. Biedroń matured. He convinced people with his rhetoric, he spoke to them, he won them over with his diligent student attitude. His predecessor, Maciej Kobyliński, was crass and bossy.” Piechociński can name only one thing that Biedroń’s predecessor did better: “Kobyliński was good at satisfying aesthetic expectations. He was like a dictator. If one day he spotted a hole in a pavement, it was patched up the next. Under Biedroń, Słupsk has become messy.”

“I didn’t like him, I thought he was a vulgar tattler. Still, I voted for him.”

But Biedroń doesn’t just want to make a good impression. Despite having only three representatives in the town council of 23 members, he consistently promotes solutions that are otherwise nipped in the bud by PiS from the top down, such as environmentalism, feminism and secular politics. Opposing the church, he started by introducing sexual education in schools and implemented subsidies for in-vitro fertilisation. He rides a bike and isn’t interested in using the limo service at his disposal. At the town hall, he has boycotted bottles and drinks tap water. Thanks to him, Słupsk’s streets are lit by energy-saving street lamps. Vacant buildings will be renovated and converted into communal flats. For a long time, he has stood against changing the city’s street names in a bid to ‘de-communise’ Poland, a law the country’s political opposition considers unconstitutional. And while in the rest of Poland PiS dismantles the separation of powers, Biedroń teaches democracy lessons at schools in Słupsk.

Still, he denies all allegations suggesting that he is running a campaign against PiS, the same way the democrats in the United States do for Trump. “The happiness of Słupsk’s inhabitants is my priority,” he says, “If I have a chance of implementing politics that benefit people, that should exist everywhere in Poland, I do it.” But Biedroń is not leading a left-wing utopia. He became mayor of the fifth most indebted city in Poland. Since then, he has not only managed to reduce the debt, but has also boosted the city’s budget and reduced unemployment to a record 4% (the national average is around 6%, e.d.). However, financial limitations hampered his ambitions to invest in new infrastructures, which evoked a strong reaction from inhabitants in Słupsk. Like a little crack in the wall, rents in communal flats rose under Biedroń.

What blooms in Słupsk

The afternoon mass in the Church of St. Mary has just come to an end. While girls in white communion dresses pass through the gate, elderly men fold pennants. In front of the entrance, the vicar Robert Górski says goodbye to the churchgoers. Does he see Biedroń’s atheism as a problem? “He is coherent in his separation of the church from the state, although I wish he advertised it more subtly. His sexual orientation doesn’t bother me. What bothers me is Słupsk’s poor conditions, things aren’t going well and the city lacks investments. I used to work in Kołobrzeg and Koszalin before. Those cities are blooming,” he explains.

But not everybody is as tolerant as Górski. In the Waldorff Park, we meet with Biedroń’s outspoken and fervent opponent. The retired woman’s harsh criticism towards Biedroń reverberates like shots from a machine gun. “The dweller of Prosta street”, as she likes to be called, is a supporter of the previous mayor who “simple couldn’t have done things wrong, because he was a local.” According to her, “Biedroń doesn’t care about Słupsk, he wants to become the mayor of Warsaw,” although there is no evidence to support her claims. “This used to be a beautiful park, now it’s just a place where the homeless sit,” she spurts, despite the fact that they actually sit along the neighbouring road. She continues: “Roses have disappeared” even if flowers can be seen in other parks across the city, “benches are scratched” when they are constantly being repainted, “he wasted money on new lighting, forgetting about the potholes” but Słupsk’s pavements don’t look any different from others elsewhere in Poland, and “he got rid of the photo of John Paul II” when Biedroń actually just gave it back to the Church. The litany of accusations is endless.

All it takes is going to another street corner and speaking to younger inhabitants to hear a completely different opinion. “The previous mayor was a thief. We have nothing to reproach Biedroń for, he is a fantastic person,” say Zuzanna and Anna, both 20 years old, walking with a stroller around the Stary Rynek, an old market. “Thanks to Biedroń, Słupsk came back to life,” they add. To prove their claims, they point to a site where a Mundial fanzone is being constructed.

“When he first ran for mayor, my kids became interested in politics. It was the first time in history that young people were proud to come from Słupsk.”

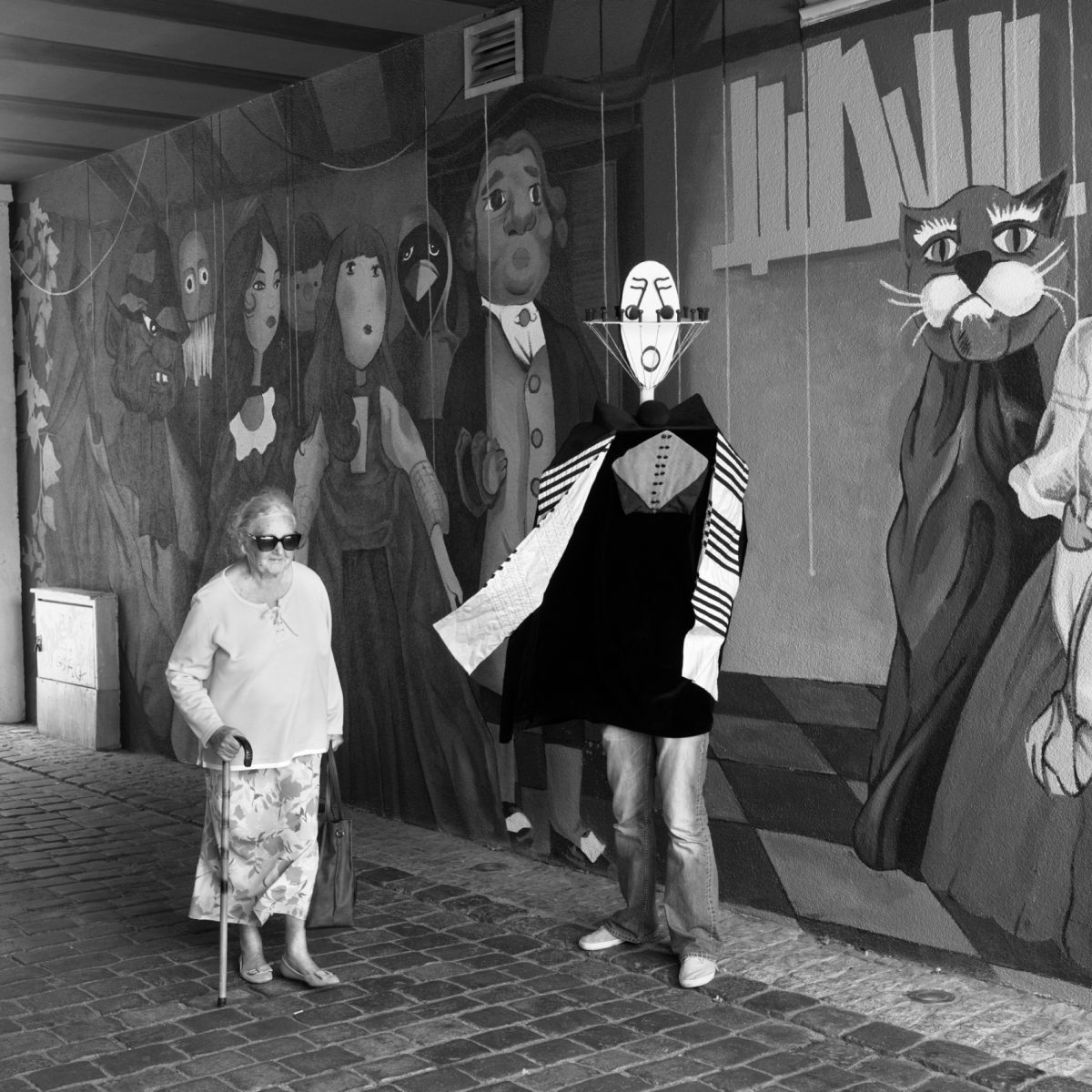

So where does the uniqueness of this pioneer city lie? Michał Tramer, the director of the Puppet Theatre “Tęcza” admits that in 2014, not many Polish cities were ready for a homosexual mayor. “If that has changed since then, it’s largely thanks to Biedroń,” he emphasises. According to him, “you don’t feel the nationalism that is ravaging the country here, Słupsk is a tolerant city. This might also be a result of its multicultural character. The proximity of the sea provides an openness to the world.” The right-wing was never very popular in Słupsk, which is the case for most former German territories. According to polls, the city’s inhabitants are one of the happiest in Poland. The unhappy minority votes for PiS. “Biedroń sheds light on the bright sides of the city,” says Daniel Odija, Słupsk’s most renowned writer. We meet in one of the many cafés that have been popping up across the city, reportedly another benefit to thank Biedroń for. “When he first ran for mayor, my kids became interested in politics. It was the first time in history that young people were proud to come from Słupsk,” Odija recalls.

People are hopeful that the “Biedroń effect” will put an end to Słupsk’s depopulation. At the turn of the century, the city counted over 100,000 inhabitants. Since then, their number has decreased to 87,000. According to Biedroń, being proud of one’s own city is “the beginning of a new chapter of development, and a way to attract investors and new inhabitants.” He defines development as investment in culture. Tramer and Odija agree with him, pointing out that vibrant cultural life is likely to attract tourists who, at the moment, are rather compelled by the seaside located only 18 kilometres away. Biedroń rejuvenated the theatre’s management by one whole generation. Tramer, whose beard fits well with his Sex Pistols T-shirt, is one of the newcomers. “I have given the theatre a makeover, I get external subsidies. We had 13 premieres over the course of two and a half years,” boasts Tramer.

Słupsk will soon have a new theatre and, in the summer, the Waldorff Park turns into an open-air stage for the philharmonic. “There is no other way to do it. All other investments will come when we invest in culture. The city has to be a good place to live, otherwise nobody will want to do business here,” the mayor explains.

The Biedroń brand

Długa Street is a three-minute walk from the town hall. It has been immortalised in Daniel Odija’s most famous book Ulica (“The Street”, e.d.). One of the buildings along the street has a wall decorated with a quote from the novel. What was once a dodgy area has now been liberated from its infamous past. And although Słupsk, sprinkled with typical secession buildings, doesn’t lack in beauty, Długa Street has seen the most drastic change. Some houses have already been renovated, while others are still waiting to be touched up. They are surrounded by a row of decaying garages with wooden doors, vestiges of a past time. Nobody is surprised at the sight of wobbling neighbours, guided by beer and light emanating from the newly-opened discount store down the street. The only person who stands out here is the mayor in his impeccable suit, posing for photos against one of the walls.

“We will be renovating all the houses one by one. And here, we will build two new ones,” Biedroń points out. “People have been complaining that we knock down their fuel sheds. However, they won’t need them anymore, because their houses will be equipped with central heating.” “And what about Prus Street?” asks one of the men working on a scaffolding. “I’m fed up with carrying coal to the third floor!” “You need to be patient, many buildings need renovation,” answers Biedroń. He smiles and greets everyone we meet on the way.

But the citizens of Słupsk will need to come to terms with the fact that Biedroń’s ambitions go beyond local politics. Some polls suggest that, if he were standing for president of Poland now, he would score third after the incumbent Andrzej Duda and Donald Tusk, who is expected to regain leadership of the opposition after the end of his term as president of the European Council. Biedroń is very active in the media and holds numerous meetings in Poland and abroad. One person even calculated that, during the first two and a half years of his time as mayor, he went around the world three times. While some hold this against him, his supporters argue that “wherever Biedroń shows up, he promotes Słupsk, even when he’s promoting himself.”

Biedroń himself explains that he represents the city for the benefit of its people. “Słupsk’s students enjoy free ice-skating lessons on the ice ring that I scrounged from the Jeronimo Martins company. They also have programming lessons thanks to my visit to Samsung. I cruise around Poland to learn about other cities from local authorities and inhabitants. I gather the best ideas, carry them in my backpack and put them in place in Słupsk,” he smiles.

He could also say that he travels across the country to teach others. “Let Poland be like Słupsk,” he repeats. But Słupsk doesn’t want to share him with the rest of Poland. “Biedroń’s transition to national politics would not only be a loss for this city, but for the notion of self-governance as a whole,” Tramer sighs, before adding: “Even though I would certainly vote for him.”