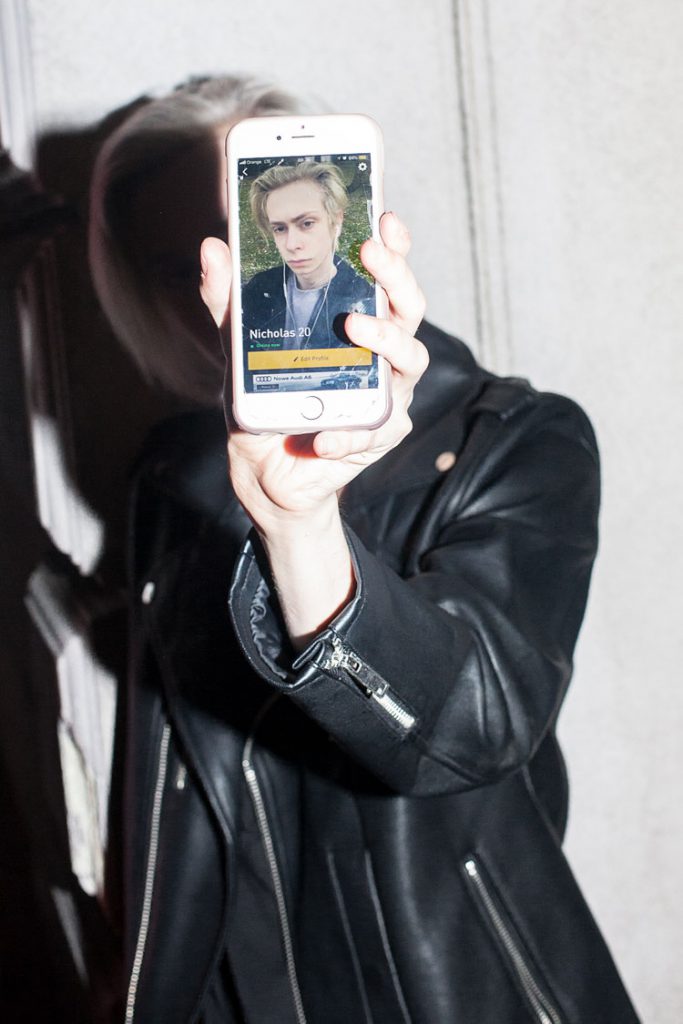

Grindr: In search of lust and love

© Mateusz Skóra

Finding love is not easy. But thanks to online dating apps like Grindr, the search for a life partner can be faster and wilder than ever. In Jelenia Góra, a small town in Poland, users have experienced anything from dinner invitations to sex offers to dick pics. The lack of real life dating options in the border town means gay men need to maximize their chances online.

80,000 people may seem like a lot at a concert or watching a football match. But dating in a city with around 80,000 inhabitants paints an entirely different picture. Jelenia Góra, a small town in Poland that borders with the Czech Republic, is an ageing place. Its largest population group is between 55 and 64 years old. Finding a potential partner in a small town whose population has passed the peak of their golden years isn’t an easy task. Being a sexual minority in that town doesn’t help, either. So what do you do when you are gay and looking for love or sex in a bounded place? You download Grindr, the most popular online dating application for gay men and women.

The world of online cruising

Grindr uses geolocalisation to show its users the people closest to them that match their criteria, acting as a platform to bridge the divide between online and offline contact. The app’s users in Jelenia Góra (and globally) can usually be divided into two categories: people who are looking for casual sex, and people who are looking for a relationship.

“It’s very easy to get your ass fucked by a random guy. But to find a guy who wants to get to know you and build a relationship, it’s almost impossible,” says 19-year-old Adam, a student in the town. He was born and raised in Jelenia Góra, and Grindr is the only way for him to connect with other gay men. There are no gay clubs in the area, no rainbow flags hanging from the windows of historical houses on the main square and no active LGBT+ community. “We do not have places here where gay people can hang out. We don’t even have a cruising area [i.e. cruising for sex] here,” Adam laughs.

Walking around the city on a busy weekday, it’s easy to feel the overbearing level of masculinity in the air. Heterosexual men seem to dominate public spaces in the small border town. Walking through the historical centre, homeless men sitting and drinking outside on benches regularly shout at passers-by. The open-air gardens in front of the city’s bars are full of men in sports jerseys, drinking beer and cheering for their national team. Youngsters who drink cheap booze and smoke cigarettes occupy hidden spots along the city walls. Seeing two men or two women holding hands and walking in this environment is almost unheard of.

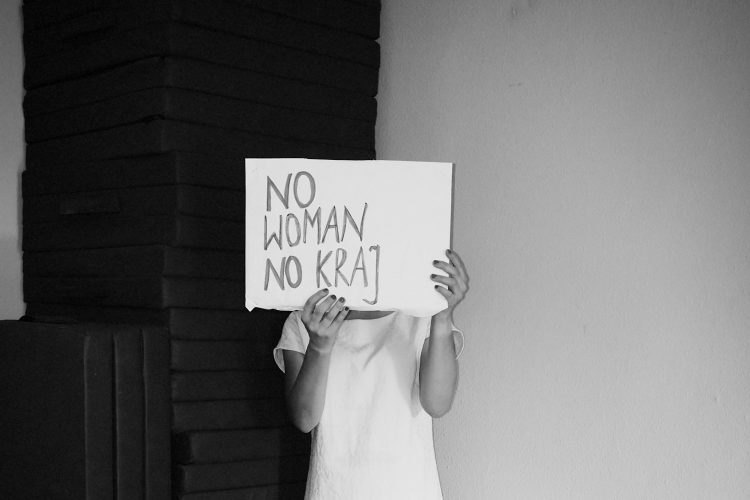

But there are always exceptions to a rule, despite the fact that Jelenia Góra is – like the rest of Poland – not very accepting nor welcoming to gay people. According to a CBOS opinion poll from 2017, 24% of Poles believe same-sex sexual activity is morally unacceptable, 55% think it’s a deviation from the norm but should be tolerated. Nonetheless, international studies such as the the latest ILGA ranking (International Lesbian and Gay Association) see Poland as one of the worst countries to be gay in Europe with the community facing gross violations of human rights and regular discrimination. So far, there is no state protection for the LGBT+ community, except for the anti-discrimination laws that were added to the Labour Code in 2003. Since then, the Polish Constitution guarantees that all persons shall be equal before the law, all persons shall have the right to equal treatment by public authorities and no one shall be discriminated against in political, social or economic life for any reason whatsoever. Subtly, but not explicitly, including sexual orientation.

© Mateusz Skóra

From dinner invitations to group orgies

Grindr and similar online dating sites are the only places where gay men can feel safe and can actually connect with other people. Often times, safety and anonymity are crucial components that the LGBT+ community in Jelenia Góra seek.

“Over the years, we have found many people here in Poland or in the Czech Republic on Grindr that became our friends. We stay in touch, visit each other or go for trips together. To be honest, I’d rather go to Prague to have fun than some other place in Poland. Czechs are more open-minded,” Dominik, a 38-year-old Pole, continues, “In Poland, as gay men, we are missing support and tolerance.” He has been in a relationship for 12 years and is now living with his partner and their children. Both Dominik and his partner have Grindr profiles, which they use to make new friends.

Searching for friends on Grindr is quite common among gay couples in Jelenia Góra. For Dominik and his partner, Grindr acts as a substitute for the lack of LGBT+ community life in the area, while for others it can also double up as a way for them to quench their thirst for casual sex. “We know a lot of people who go to the Czech Republic to have sex. There are well-known places that host sex parties. In Jelenia Góra we all know each other, so if someone wants to stay anonymous, they just hop over the border. Grindr can give you a sense of anonymity, if you want to stay anonymous [that is],” Dominik clarifies. Grindr is a bit like Russian roulette; users can land on anything from simple dinner invitations to group orgies.

Pawel, a Pole in his thirties, uses the app since it was made available and lives together with his partner close to Jelenia Góra. He finds most of his connections outside of the town´s walls. “It is very easy and safe for us to find someone who is interested in having sex with us on Grindr,” says Pawel, who has been using Grindr for five years without ever revealing his true identity. “Together with my partner, we want to explore sex and its variations, so we look for other men to join us. We slept with guys from Czech Republic, Germany, Russia and Poland. We have this one Czech guy who is married, but comes once in a while to Poland to fuck,” Pawel explains. Him and his partner make it clear what kind of offer guys can expect from their profiles.

“Grindr is limited by location, but also by mentality”

One of the benefits of using Grindr in border towns like Jelenia Góra is that users see people living very close to them, on the other side of the border. In the past, when the border was still present, visible and not easy to cross, it was unusual for people to search for love in the neighbouring state. They would come for work and find love haphazardly.

“There are plenty of heterosexual mixed marriages between Czechs and Poles in the Krkonose area. My dad is Czech and he was pretty courageous to find a Polish wife. He was even very motivated, because Polish women are known for being pretty. It took them a few dates to break the language barrier and then I was born,” says Martin, a 35-year-old Czech man living in Vrchlabí, a town just 30 kilometres from Jelenia Góra. He has been using the app for the last three months.

“I don’t know if you can find love here. Because I am not sure if the connections you make on Grindr lead to more than two dates. Dating apps are serving you a full plate of faces and information, and I think that more you see the more you want. Which means that with so many options, men are tempted not to stick with one, but explore as much as they can,” Martin admits. He adds that most of the messages he receives have sexual connotations, and that isn’t something he is looking for at the moment. When asked about his experience with Polish guys, he mentions his appreciation for their straightforward-ness. “If they aren’t seeking a quick discreet fuck, they usually say they want to meet someone and get to know them. But I haven’t met anyone yet.”

Maciek, an artist currently living in Jelenia Góra and working on a project about the town’s history, voices the same doubts about finding love as Martin. His precise words when describing Grindr are: “It is the last option to meet someone.” His experience with the app was shaped by using Grindr in a bigger city like Wroclaw or Warsaw, where there is more anonymity between users. “Once I logged in in Jelenia Góra, I became a fresh face and everyone wanted to talk to me. The interest faded away after a while, and then the enthusiasm turned into hate. People started attacking my looks, saying I’m too hairy and whatnot,” Maciek explains, “I think that Grindr is limited by location, but also by mentality.”

For Maciek, there is a sense of safety that can be preserved online. “I talk to guys online. We exchange pictures and we chat. But when I walk around the city and meet one of them in real life, they just ignore me. They look away and pretend that they don’t know me. It’s something that doesn’t happen to me in bigger cities.”

The small town mentality and fear of being ostracized might be limitations for some men, especially those who have a hard time finding the courage to take the connection from an online to an offline space. But for others, real life interactions are more valuable, and that’s where Jelenia Góra can be limiting. The town lacks safe spaces in which the LGBT+ community can be themselves and express their affection openly to one another.

Creating safe spaces

Rita Schaeper wants to change the “toxic” environment and create a safe space for LGBT+ people in the border town. Rita is a German artist, musician and psychotherapist who has been living in Poland since 1997. Last year, she founded Grupa Rozwojowa LGBTQ in Jelenia Góra, a support group offering a safe haven for members of the community.

“I am a lesbian, and my goal was to open a place for people who describe themselves as non-heterosexual. I wanted to have a place to meet, to grow and to talk about problems connected with being gay. I wanted to create a space where they could meet other people that are in similar situations, and talk about issues concerning love or coming out to your family,” Rita explains, taking a sip of her tea.

The support group takes place every Wednesday in her apartment in the centre of town. “The young people who join represent a certain progress in the Polish mentality that has come to fruition over the past 20 years that I’ve been living here, and I’m very happy about that. When I came here, it was very hard to find someone who you knew was non-heterosexual. These days, when you ask young boys and girls they will tell you: ‘if someone asks me, I will tell them. Why not? If they have something against it, it’s their problem not mine.’ They are much more confident about their identity,” Rita says, reassured.

While Rita has noticed a newfound indifference to public opinion among the area’s LGBT+ youth, men in small town usually decide not to put their faces on their Grindr profiles, showing parts of their body or headless torsos instead. When opening the app in Jelenia Góra, there are about two profiles with clear headshots for every 35 users. The rest are unrecognisable.

One of the younger generation’s loud and proud gay men is Bartek, a 25-year-old bartender who just recently moved to the city. Bartek refuses to hide his identity. He came out to his family and to his work colleagues. He says that his sense of humour and kind personality helped him to avoid troubles that might be caused by him being openly gay.

“One of my ex-boyfriends lives just a few kilometres from here. If I wasn’t using the app, I would probably not have known about him at all.”

Bartek uses Grindr every day to connect with people. “I receive messages from Czechs, Germans and Poles. But I usually talk to the Polish guys. I see them on Grindr, then I see them on Instagram and I also see them in real life, so I can pretty much figure out what their deal is and what they are up to,” Bartek says, proudly joking that he could be a detective with the amount of investigate work he takes on in his dating life. He is also very enthusiastic about finding love online and the possibilities Grindr brings to him. “I like seeing people who are gay and live nearby. If I find love somewhere and I have a car, I wouldn’t mind driving

40 or 50 kilometres. I already did that once in my life,” he admits.

The appreciation for having a possibility, albeit a limited one, to connect with a stranger is something Bartek has in common with Marcin from Świeradów-Zdrój. Marcin’s hometown is small, like Jelenia Góra, and situated just three kilometres from the Czech border. The 25-year-old wine merchant comes here to visit his family and has embraced online dating as a natural part of his love life. “I met both of my ex-boyfriends on Grindr. One of them lives just a few kilometres from here. If I wasn’t using the app, I would probably not have known about him [at all],” he says.

Marcin is one of over three million men who use the app daily across the world. By being visible online, he increases his chances of standing out in a ‘crowd’ of 80,000 people. Whether it’s lust or love, Jelenia Góra has more to offer than meets the eye. All it takes is a little scratching beneath the surface, and having an open mind when it comes to dating applications like Grindr.

Given the current situation in Poland, online spaces still offer more possibilities for the LGBT+ community to connect than the sometimes-harsh reality of offline spaces. Still, the small border town is no exception – the only true safe spaces for gay men living in town are found behind closed doors of their homes.