The shifting ground that is women’s football in Poland

Patrycja waiting for the match to begin. @Katarzyna Mazur

The female members of the MKS Olimpia football club in Szczecin, who made it into the First League in 2015, often feel they are representatives of a niche sport. But this successful girl gang is a small miracle in a country that is constantly challenging the role of women in society.

Training is about to start for the female division of MKS Olimpia, Szczecin’s football club. Nicknamed “the Olympians” by locals, the young football players wear matching blue kits. Each and every one of them comes from a different place, has a different background story and different dreams, but the one thing that unites them is their common love for the sport. The club is their microcosm, a point of reference of sorts, a prism through which they view the world. For the girls, their first priorities are the club and their personal lives.

Before they walk out into the field, it’s time for an update. Today’s hot topic is high school final exams, which some of them are in the midst of taking. Maths was especially difficult this year, Polish went all right. Then comes hair, shoes, nails and makeup. “Please edit my braces out of the photo,” one of the players asks, posing for us with a big smile.

One for all, all for one

The rules on the pitch are clear. There is no room for interpretation, questions or doubts. “Move girls, this is football!” This is what they love; once in the game, they can relax and forget all about their worries and troubles. Everything is about the here and the now, everything revolves around the ball. Everyone is in their element. “Left foot… what is your right foot doing there?” On the neighbouring field, a team of junior players – seven and eight year old girls – are training. The coaches of both teams exchange a brief “siema” or “hiya”. They address the players by their surnames: “Ratajczyk is injured.”

No matter the weather conditions, trainings take place on Mondays to Fridays at Szczecin’s Pogoń stadium, a top of the league football club that is fully masculine. The Olympians play alongside the Pogón players, all men and boys of different ages. Piotr Spunda, one of MKS Olimpia Szczecin’s four founders (who are all former referees), explains that it has been around for 13 years and has always been a women’s only club. In fact, Olimpia is the only women’s football club in town and is currently ranked sixth in Poland’s so-called “Extraleague”, the top football league in the country. It’s the highest the team has ever ranked in all its history.

Florian Krygier stadium, Szczecin. The girls from MKS Olimpia are warming up before their training. @Katarzyna Mazur

The players spend a lot of time together, both on and off the field. Some of them, especially those who don’t come from Szczecin, share the same flat or dorms. “Even if in our private lives, not all of us are friends but on the field we are a team,” Weronika Szymaszek, the team’s left-back defender and a first year student at Kamień Pomorski’s University of Physical Education, explains. She’s been with Olimpia for three and a half years. Roksana Ratajczyk, who is also in the junior Polish league (up to 19 years old), adds: “We’re a family on the field and off the field.” Beata Niesterowicz, a player and a PhD student at the Institute of Mechanical Technology in the West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin, has started to see the bond as a sort of therapeutic necessity: “There are moments in which we’ve had enough of one another, where all of us come to training pissed off. But after a long break, we realise how much we miss this kind of contact with one another.”

Most of the team’s players come from Poland, but two come from Ukraine and one from Germany. Many of them see their membership as an opportunity, even if they miss being home from time to time. Despite the proximity of the German border, the Polish players are not interested in emigrating. They identify with the club more than they identify with the city they live in. And when they do travel abroad, it’s for friendly matches. “Usually, we go, we play and we come back,” Patrycja Trzcińska, who has been in Olimpia for seven years, says. She doesn’t have time to speak to players of foreign teams. Originally from Koszalin, she moved to Szczecin to start her studies in IT. Only one of the players from the club admitted she could imagine a life and career outside Poland’s borders.

It’s a man’s world

When asked why they didn’t choose to become ballerinas or volleyball players, the girls laugh. “Many people, especially men, don’t get it,” Beata says. “Once, a man approached us and said: ‘Nice girls, beautiful, what are you playing?’ When we say we’re playing football, most men are pretty surprised. They usually associate a girl’s sports club with handball or volleyball.” In a serious tone, Beata concludes her story: “Football is a brutal sport. Injuries can disable a player for as long as half a year. Men are surprised that women are even interested in this sport.”

In most cases, however, it was fathers and brothers who first introduced the girls to football. That was the case with Patrycja, who initially only played in male teams where she was treated as an equal. She got along well with the team members. “Before puberty, [men and women] play the same way, we even look similar. It’s only later that the differences become visible,” she says. “My brother would say I couldn’t shoot, so I always ended up being the goalkeeper. I still am to this day,” laughs Beata.

“Before puberty, we play the same way, we even look similar. It’s only later that the differences become visible.”

“‘Football? Really?’ We used to get that question a lot, but we’re finally starting to get some recognition. People are starting to say: ‘In that case, I’m sure you play for Olimpia’. And in Poland, there isn’t a higher league we could play for. If games were broadcasted on TV, it would help us a lot. At least that way sponsors could find us more easily,” Patrycja says. Beata agrees: “Ten years ago, nobody thought a woman could play football. Luckily, things have improved since then.”

When asked whether this attitude towards women in football is somehow related to Polish politics or is in any way a Polish phenomenon, the girls either respond with silence or denial. “Bigos (a Polish hunter’s stew, e.d.) is typically Polish,” Beata responds sarcastically. The Olympians argue that in France, Germany or Scandinavian countries, women’s football has a different status and gets more attention. They argue that, in these countries, players earn more money and aren’t subjected to mockery. The girls talk about FFC Turbine Potsdam, whose matches can sometimes attract thousands of spectators. Olimpia’s coach, Natalia Niewolna, elaborates: “We still need a lot of time to catch up with them (FCC Turbine Potsdam, e.d.). Women’s football matches in Poland gather up to a maximum of 5,000 spectators. Our record was 500. That was four years ago, during the league’s first match against the Sztorm Gdańsk women’s football club. We had to promote the game ourselves and paste posters all across the city. In 2011, during a qualifying match in Dresden, where the USA played against South Korea, there were 75,000 spectators. The stadium was bursting at the seams. Here, it’s another world.”

In Poland, women find it hard to fully invest themselves in football. According to the girls, it is mostly due to the low salary a female professional football player will earn. Many players end up changing paths and finding a more lucrative job after they turn 20. They see no future in football. “At some point, you have to think about making a living,” Beata says, bitterly. What’s more, the system doesn’t exactly work in their favour. Women have a hard time making the transition from junior to professional teams because of the age limit; while male football players can play in junior leagues up until the age of 21, making for a smoother transition into professional football.

Weronika’s case is proof. She says she would love to continue playing professionally, but that she can’t imagine that happening in Poland: “We are stuck, paralysed. We become jaded seeing the boys from the fourth division going far while they only train three times a week.” “Of course, this upsets us,” the Olympians says unanimously, “but we can’t change it. We are trying to fight for our cause, but it requires patience.”

“The only thing we have in common is using our legs to play with a ball.”

The girls say that one of the biggest struggles is the fact they are constantly being compared to men. To them, female football is not the same as male football. “The only thing we have in common is using our legs to play with a ball. Our matches and trainings are completely different,” Patrycja explains. “We sometimes hear stories of how a women’s team lost to some male amateurs. We aren’t being taken seriously. In Poland, no one believes that girls can be good football players. Sure, men may be physically different, but in terms of technicality and ambition? No,” Beata says, visibly annoyed.

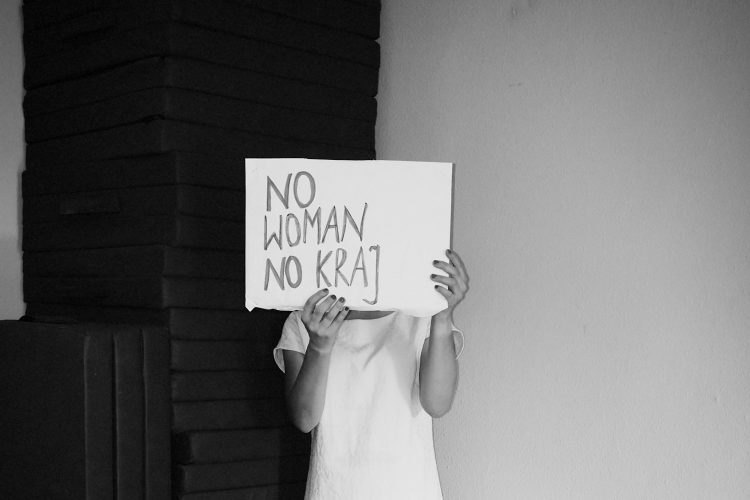

Everything is political

The girls don’t feel represented or supported by the Polish Football Association (PZPN). They claim it is because the association doesn’t believe in the Olympian’s potential. The topic is a recurring one among most members of the club, and right now there is one burning issue: the PZPN refuses to accept Olimpia’s appeal, in which the players demanded a re-evaluation of one of the match outcomes. For many, it is concrete proof that the association’s politics may have a direct affect on their club and its members. What happened was that Olimpia Szczecin lost 0:1 to Czarni Sosnowiec in semi-finals. After the game, they found that one of Czarni Sosnowiec’s players wasn’t on the match roster sheet, which goes against the rules of football. If it were a men’s match, the PZPN wouldn’t have accepted the final results. But in this case, the PZPN decided to keep the score.

Roksana, waiting to recover from her foot injury, is stretching her legs. @Katarzyna Mazur

Piotr Spunda reckons that this is symptomatic of the PZPN’s general attitude towards women’s football. The association tends to treat it like a neglected stepchild, adding a solid dose of sexism to the mix. And there is barely a need for proof. Zbigniew Boniek, the chairman of the association, tweeted: “When we speak about football, a woman’s input is useless.” On the PZPN website, there is a short film advertising women’s football. It ends with a quote: “Football is beautiful, as are Polish women.”

“When we speak about football, a woman’s input is useless.”

“We need to wait a very long time for decisions [to be taken] and we don’t feel supported by the association. We are trying to defend our players’ rights and fight for them. Ours is no longer a niche discipline. We deserve more serious treatment and recognition,” Piotr exclaims. Thankfully, it seems as though the town hall in Szczecin is more supportive. Local authorities have always been sympathetic to the club’s problems. “Locally, this [Olimpia] works way better than on a national scale. It’s not surprising, though, given the fact we’re not taken seriously even by the PZPN,” the ex-referee sighs.

The players themselves don’t seem particularly eager to stand up for their rights. Although the situation “pisses them off”, they are happy to let others fight for them. “Nobody understands why things work this way in the PZPN. Money must be one of the reasons. Still, it’s our chairmen, trainers and leaders who deal with it. I focus on playing and don’t want these things to distract me from the game,” one of the players explains. The same lack of interest is expressed when it comes to national politics. When asked about the current situation in Poland, most girls answer that they’re not at all interested in the topic. Of those over 18 years old, only one voted in the past elections. “Politics is too agitating for me. I’m not interested,” Patrycja, Aleksandra and Weronika say. “It’s bullshit. Whatever’s going on in the parliament is just not my cup of tea,” another girl adds.

They don’t think that Polish women’s rights are in danger because they claim they don’t see threats in their immediate surroundings. “But if you think about this mess around our Polish Cup…,” Patrycja Michalczyk recalls after pausing, “there are some rules that should be obeyed. It’s the case for men’s football, but not for women’s.” Aleksandra prefers to talk about gender differences: “Men are faster, but women have more heart.” Natalia, the trainer, also chimes in: “A woman will put her head where a man wouldn’t dare put his foot.” It is important to remember that there is a beginning to every grassroots movement. “We will fight in our own backyard,” Natalia concludes.