Abortion in Poland: My body, your country, my choice?

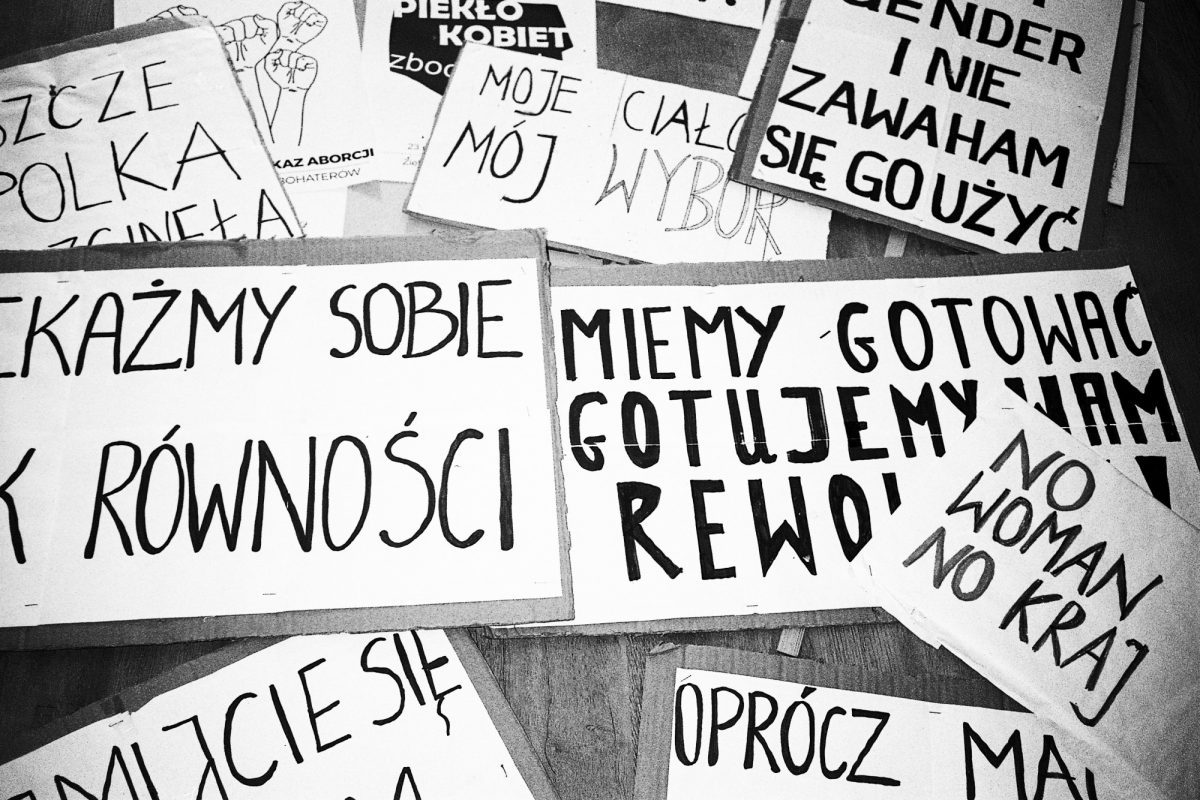

The famous Polish women rights campaign slogan reads: "No woman, no country" © Anna-Kristina Bauer

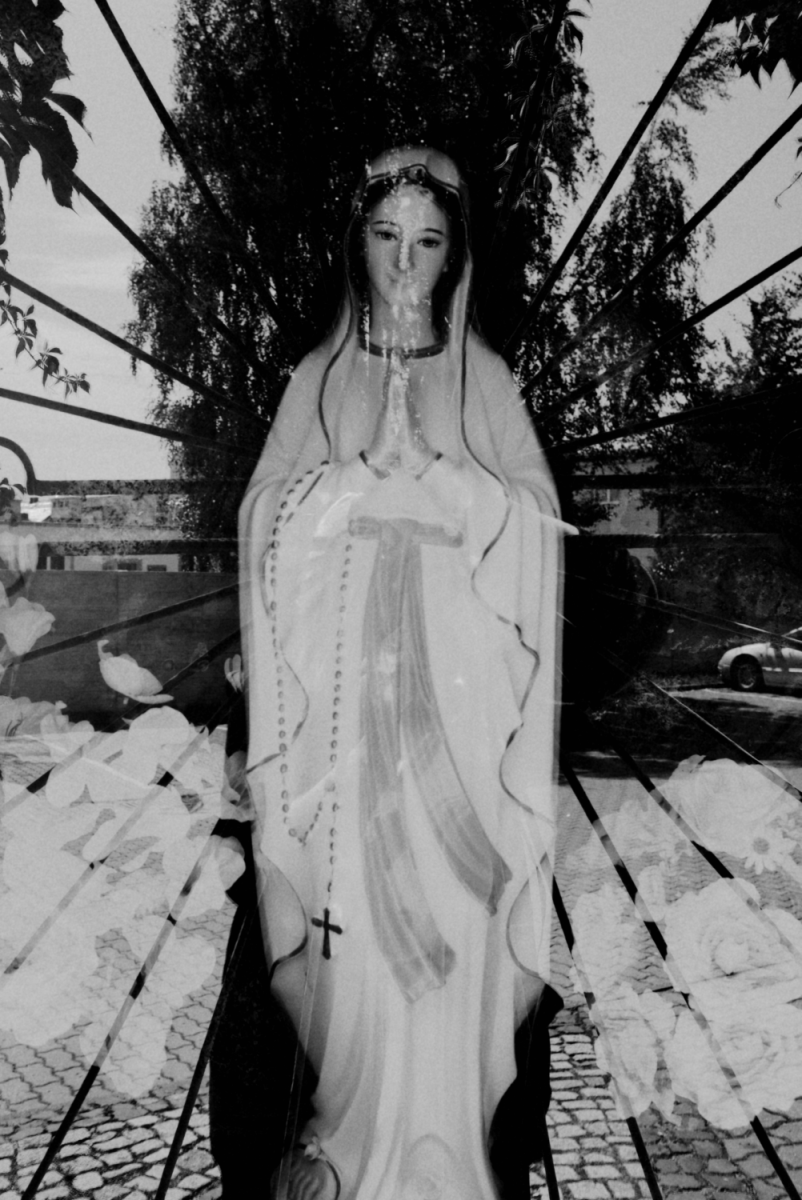

Catholic Poland is one of the rare countries in Europe where women don’t have free access to abortion. And as if that weren’t already enough, the right-wing populist government is trying to tighten the existing laws. Thousands of Polish women are forced to seek help abroad, including in Germany.

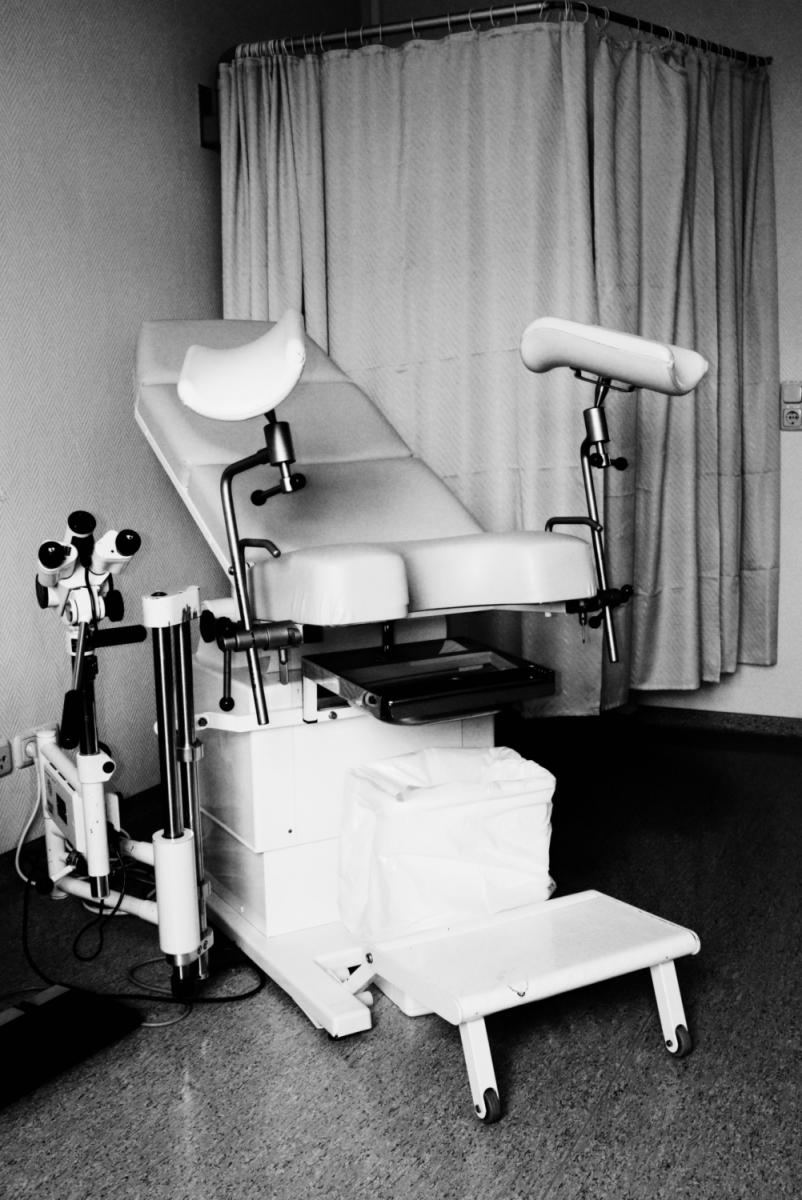

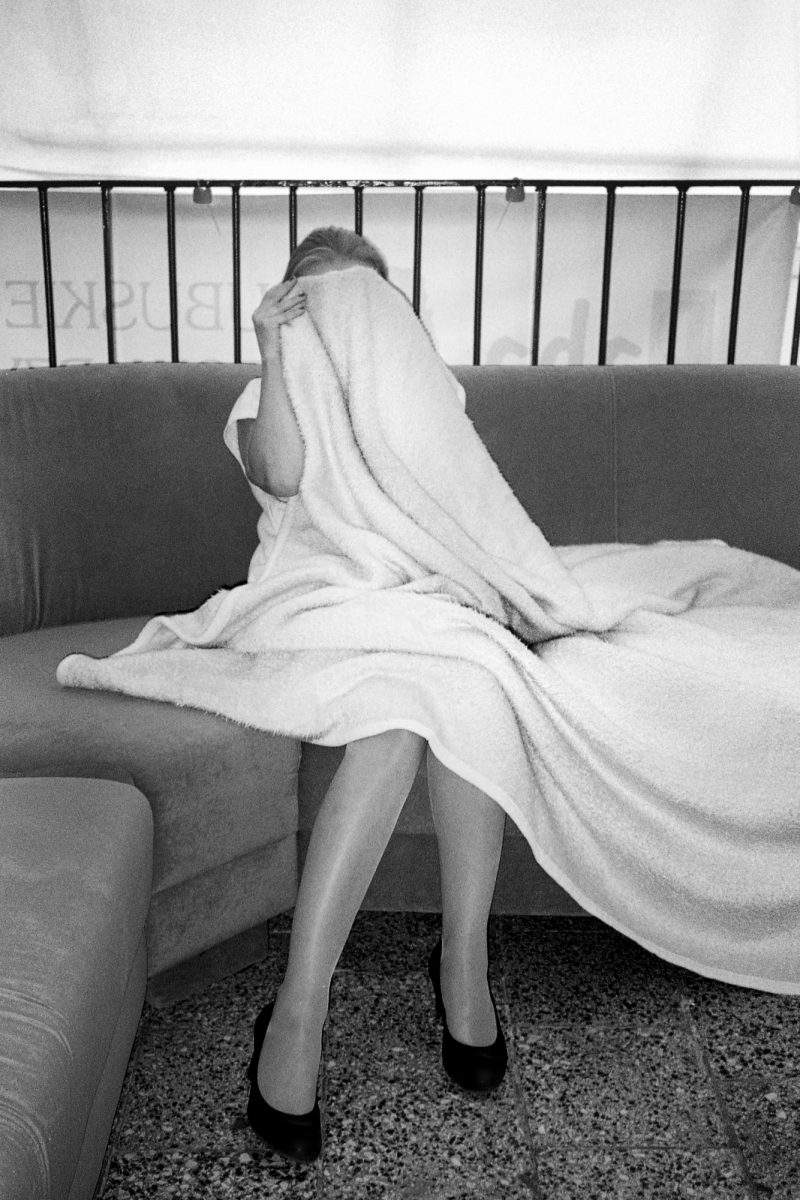

“The worst moment was in the beginning, when I found out I was pregnant. In Poland, the baby counts more than the mother, who could die saving the life of the baby. Germany is a different world. Here, you can count on getting help without being judged,” 30-year-old Kasia is lying in the bed of her bright and empty hospital room in Prenzlau, a provincial German town near the Polish border. Her husband is beside her. She looks downcast and pale, having just recently awoken from the anaesthetised sleep for her abortion. When she speaks, her oval cheeks darken with anger.

“I didn’t want to get pregnant in the first place. I have cancer, I need to heal. But it happened, our contraceptive methods didn’t work. When the gynaecologist found out I was pregnant, he got angry with me at first. Then, he said that although he wasn’t entirely sure, the pregnancy could influence the course of my illness. But since he couldn’t prove that with 100% certainty, he said he couldn’t help me,” she explains.

“Will the priest find out?”

In Poland, abortion is legal only in three cases: if the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest, when it endangers the mother’s life and when the foetus has a congenital disorder (birth defect, e.d.). Even in these cases, there is no guarantee of a right to abortion. Doctors are scared of carrying out abortions, because if somehow the procedure is proven illegal, they risk up to three years in prison. “When the gynaecologist heard the word ‘abortion’, he was outraged. He said: ‘This act is an act of killing, and you should beware, it will always come back to you.’ Regarding my life, however, he didn’t seem to care as much.”

Needless to say, the restrictive law doesn’t stop women from terminating pregnancies. While the number of legal abortions in Poland fluctuates around 1,000 per year, the Federation for Women and Family Planning estimates that up to 150,000 illegal abortions are carried out in the country each year. According to a study by the Centre for Public Opinion Research (CBOS), every fourth or even third pregnancy is terminated. The frequency is partially explained by the lack of sexual education in Polish schools, where ‘family life’ classes are taught by priests.

Polish women who want to get an abortion either look for doctors on the black market, buy pills online or go abroad. Those who live in the western part of the country, like Kasia, mainly go to Prenzlau in Germany. Kaia comes from Świebodzin, a small town in the Lubuskie voivodeship. Although Frankfurt an der Oder is closer, Prenzlau has a Polish doctor. His name is Janusz Rudziński and with him, women don’t have to worry about the language barrier. Doctor Rudziński is a star on women’s forums and has been called a “saviour” and “the friend of Polish women” by members.

“Women come from all four corners of Poland,” Rudziński admits. “From schoolgirls to university professors. I have terminated pregnancies of wives of conservative political activists, mistresses of priests and even a nun. Contraception doesn’t always work and isn’t accessible to people living in small towns. I once had a patient whose doctor refused to give her contraceptives. He gave her sedatives instead.” Under Polish law, doctors have the right to refuse the prescription of contraceptives by evoking the so-called conscience clause. In big cities, it’s less of a problem than it is in smaller towns, where the number of doctors is limited and sexual life is a taboo topic.

“I once had a patient whose doctor refused to give her contraceptives. He gave her sedatives instead.”

But abortion is even more of a taboo. Even if women who have an abortion are not penalised for it, it is difficult for them to escape stigmatisation. In Poland, it’s not uncommon to liken abortions to “murdering an unborn child”, “homicide” or “Satan’s triumph”. This pro-life discourse, often marginal in other countries, is what is most commonly used in the Polish debate around abortion. When asked about his patients’ biggest fears, Rudziński gives a concrete answer: “Women from eastern Poland mostly fear priests. They don’t fear god because, as they say, god is far away and knows mercy. Priests are close enough and don’t know mercy. When they first come in, some of my patients ask me whether or not their priest will find out what they will do.”

Most of Rudziński’s patients leave the cabinet without a medical certification. They want to remove all traces. “But I remember one patient who did take the document. After one year, she called me in tears saying that she had a fight with her fiancé. He had taken the certification and showed it to the priest. It was awful. She had to leave her village because people had started calling her a ‘murderer’.”

Crime and punishment

The situation doesn’t look much better in western Poland, despite the fact that – according to statistics – it is more secular. “A young girl came to see me. She was raped by her father and got pregnant,” Dr. Anita Kucharska-Dziedzic, the founder and president of the Association for Women BABA in Lubusz, recalls. “She was 14 years old, too young to represent herself in court. She could have had a legal abortion if it weren’t for her mother who opposed the idea, saying that ‘one sin in her house was enough.’ The girl was forced to give birth to a gravely disabled baby.”

BABA is the only feminist NGO in the region. It runs anti-discrimination campaigns and helps victims of domestic violence. BABA sometimes receives calls from women who want to have an abortion. They ask which German clinics are trustworthy. Sadly, BABA can’t help them with this, since advising or “assisting in an abortion” is punishable by law and can result in a prison sentence. “Once, a school psychologist called us and told us that a student had confided in them. She had had an abortion with the help of her mother. The psychologist didn’t know how to deal with the situation, and didn’t reckon they could keep the student’s confession a secret. The psychologist ended up going to the prosecutor’s office and filing a statement against the girl’s mother, indicating that she had committed a criminal offence by choosing to help her daughter have an abortion.”

Even in big cities like Zielona Góra, the capital of the region, women prefer hiding the fact that they’ve had an abortion. Natalia is one of them. She had an abortion two years ago but only told her closest friends. “I was using protection, the pregnancy came as a surprise,” she recalls. “I took four tests and all of them were positive. But I didn’t go to a gynaecologist in Poland. I didn’t want to leave any evidence of my decision behind. I was sure of what I was doing, I already have on child and I didn’t want more. What’s more, I was almost forty at the time and on hormonal treatment.”

Following the example of many other women from the region, Natalia headed to Prenzlau. “Once on the road, I realised that there was a blessing in disguise. I withdrew some cash, about 400 euros. I took my car, switched on my GPS and went to Germany. Not all women have this kind of freedom, some have to count every penny or don’t have enough money at all. They can’t take this decision. I was scared after reading some women’s forums. Some women write that they can’t afford an abortion abroad and advise each other to overdose on medication, causing a miscarriage.”

“The fact that I was forced to go abroad was absurdly cruel.”

Despite the wide plethora of inequalities, there is something that all Polish women who have had an abortion have in common: humiliation. “The fact that I was forced to go abroad was absurdly cruel,” Natalia explains. “I felt the hostility of the Polish state on my own skin. I’m not granted the choice of being a mother or not, and when I decide to become one, I’m not given decent maternal care. If my baby is born sick, I can’t count on any support from the state. Getting a spot in a day nursery or a kindergarten is a miracle. Yet despite all this, women are still judged for what they do and believe.”

The Black Protest

Although Polish abortion laws are some of the strictest in Europe, the Catholic Church and its grip on politics hopes to ban the practice altogether. The Church wants to force women to keep the baby even in the case of rape, danger to the mother’s life or a congenital disorder of the foetus. In 2016, the Catholic organisation Ordo Iuris submitted a draft bill proposing the removal of these three exceptional cases that allow for a legal abortion. The bill even suggested criminalising the act, punishable by years in prison. Many members of the ruling right-wing populist Law and Justice (PiS) party have expressed similar views, as the party itself is dependent on the Church. However, in the aftermath of mass demonstrations during the Czarny Protest (also known as “Black Protest”), the ‘stop abortion’ bill was rejected.

Anti-government protests have become the norm in a country so polarised. The Black Protest didn’t only mobilise women from large cities, women from smaller towns also took part in the protests. Among them were women of Słubice, a town of roughly 18,000 inhabitants and twin to Frankfurt an der Oder. It was here that in 2015, the Women on Waves happening took place. During the event, a German balloon with morning-after pills landed in the city. A year after that, the Słubice Black Protest gathered several hundred people, a record.

Like everywhere in Poland, Słubice’s inhabitants are divided on the topic of abortion. While one woman in a shop says “I never met the murderers, because I don’t hang out with pathological people,” another assures us that she participated in the protests. We tried speaking to priests, too, but one of them was baffled by my question and the other one refused to answer. “The Black Protest attracted the opponents of the new abortion law, as well as people who are in favour of it becoming more flexible,” says Natalia Żwirek, the initiator of the Słubice Black Protest. “It’s a small town but with a rather open-minded population, maybe because of the vicinity of Germany.”

So far, the Polish government hasn’t managed to further restrict the abortion law. However, it punished women’s organisations. “We cannot count on any subsidies from PiS,” exclaims Anita Kucharska-Dziedzic from BABA. “In the past, female victims of domestic violence could rely on our support before court trials, or get temporary housing. Today, we run on volunteers and offer as little as consulting. We can’t grant women safety. For this reason, the number of women contacting us is dwindling.” The day after the protests, the police raided BABA’s headquarters and, without any explanation, confiscated their documents containing sensitive data on women who contacted the organisation. Several other women’s NGOs suffered similar intrusions.

The small border town Słubice in protest mode about the recent laws on abortion and judicial reform (pictured) © Anna-Kristina Bauer

“We believe in women’s empowerment. Polish society is way more liberal than its politicians,” says Anita Kucharska-Dziedzic. It’s a fact. According to IPSOS polls, 30% of Poles are for the liberalisation of the abortion laws, 45% want to keep them as is and only 17% are openly against it. In the parliament, however, none of the parties have suggested relaxing the existing laws. “Politics-wise, we are living in hard times. But if we compare this to what was happening in the past decades, today’s events could be seen as a success,” adds Ilona Motyka, another BABA member. “We have seen the enactment of the Anti-violence Convention and the establishment of the official penalisation of domestic and sexual violence.”

Polish women still don’t have free access to abortion. But the Black Protest and the #MeToo movement made women’s voices hear all around the world, even in conservative circles. “Polish women eagerly cheered the Irish and the Argentinians,” Agnieszka Dziemianowicz-Bąk, one of the Black Protest initiators and a member of the left-wing Razem party, says. “We are proud of them, their fight was taking place in equally as difficult conditions as ours. Their victories fill us with hope.”

*the names of some women have been changed